Taj Mahal is an ambassador of Shah Jahan's strong interest in building and artistic innovations. The new architectural style includes aspects that were to impinge much of subsequent Indian architecture. Symmetry along two sides of a central axis, new columnar styles, curvilinear forms, and symbolic decorations based on naturalistic plant motifs are all characteristics of the Shahjahan style that can be found in the Taj Mahal Complex.

Prelude

The mausoleum is entirely clad in white marble. Alluding to the stone's luminosity, the Mughal poets compared it to early dawn or to a cloud. Kalim wrote:

It is a [piece of] heaven of the colour of dawn's bright face, because from top to bottom and inside out it is of marble - Nay, not marble because of its translucent colour (av-u-rang) The eye can mistake it for a cloud.

Kanbo refers to “the illurruned tomb (rauza-i-munauwara) on who’s every stone slab from early morning until late evening the whiteness of the true dawn is reflected, causing the viewer to forget his desire to move towards the highest heaven”.

Concepts

Under the reign of Shah Jahan the symbolic content of Mughal architecture reached its peak. Inspired by a verse by Bibadal Khan, the imperial goldsmith and poet, and in common with most Mughal funerial architecture, the Taj Mahal complex was conceived as a replica on earth of the house of Mumtaz in paradise.

This theme permeates the entire complex and informs the design and appearance of all its elements. A number of secondary principles were also used, of which hiearachy is the mostdominant. A deliberate interplay was established between the building's elements, its surface decoration, materials, geometric planning and its acoustics. This interplay extends from what can be seen with the senses, into religious, intellectual, mathematical and poetic ideas.

Symbolism

In the Taj Mahal, the hierarchical use of red sandstone and white marble contributes manifold symbollic significance. The Mughals were elaborating on a concept which traced its roots to earlier Hindu practices, set out in the Vishnudharmottara Purana, which recommended white stone for buildings for the Brahmins (priestly caste) and red stone for members of the Kshatriyas (warrior caste). By building structures that employed such colour coding, the Mughals identified themselves with the two leading classes of Indian social structure and thus defined themselves as rulers in Indian terms. Red sandstone also had significance in the Persian origins of the Mughal Empire, where red was the exclusive colour of imperial tents.

Its symbolism is multifaceted, on the one hand evoking a more perfect, stylised and permanent garden of paradise than could be found growing in the earthly garden; on the other, an instrument of propaganda for Jahan's chroniclers who portrayed him as an 'erect cypress of the garden of the caliphate' and frequently used plant metaphors to praise his good governance, person, family and court. Plant metaphors also find a commonality with Hindu traditions where such symbols as the 'vase of plenty' (purna-ghata) can be found and were borrowed by the Mughal architects.

Sound was also used to express ideas of paradise. The interior of the mausoleum has a reverberation time (the time taken from when a noise is made until all of its echoes have died away) of 28 seconds providing an atmosphere where the words of the Hafiz, as they prayed for the soul of Mumtaz, would linger in the air.

Interpretation

The building was also used to assert Jahani propaganda concerning the 'perfection' of the Mughal leadership. Wayne Begley put forward an interpretation in 1979 that exploits the Islamic idea that the 'Garden of paradise' is also the location of the 'throne of god' on the day of judgement. In his reading the Taj Mahal is seen as a monument where Shah Jahan has appropriated the authority of the 'throne of god' symbolism for the glorification of his own reign. Koch disagrees, finding this an overly elaborate explanation and pointing out that the 'Throne' sura from the Qu'ran (sura2 verse 255) is missing from the calligraphic inscriptions.

This period of Mughal architecture best exemplifies the maturity of a style that had synthesised Islamic architecture with its indigenous counterparts. By the time the Mughals built the Taj, though proud of their Persian and Timurid roots, they had come to see themselves as Indian. Copplestone writes "Although it is certainly a native Indian production, its architectural success rests on its fundamentally Persian sense of intelligible and undisturbed proportions, applied to clean, and uncomplicated surfaces."

Elements

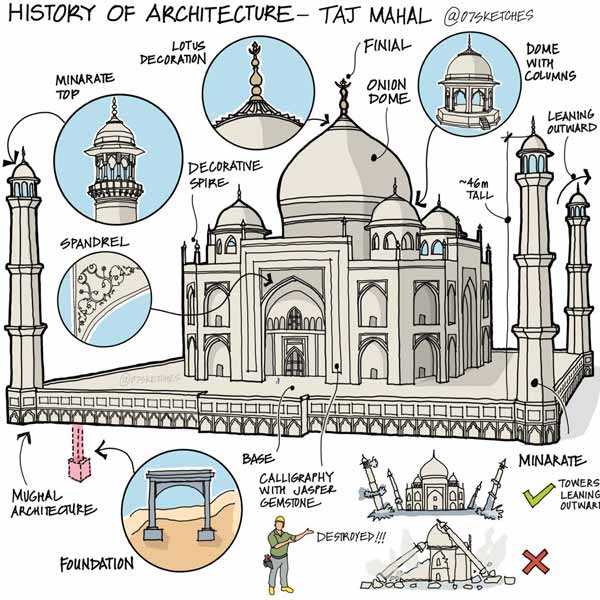

Uniformity of shapes has been set in a particular hierarchical accent. One type of column, called the Shahjahani column is used in the entire complex. It has a multi-faceted shaft, a capital builtup from miniature arches, concave elements and a base with four multi-cusped arched panels.Proportions and details of the columns vary according to their position in the complex; simplest in the bazaar streets, larger and richer in the funerary area.

The chief building of the entire complex is the mausoleum and the most naturalistic decoration appears here. The flanking buildings; the mosque and mihman khana [Guest House meant only for assembling for prayers] share mirror symmetry and display less naturalistic and less refined ornament; in the garden buildings, it is used only sparingly; and none appears in the Jilaukhana or the bazaar and caravanserai complex. The elements of the subsidiary units are arranged with the same mirror symmetry. Integrated into the overall qarina symmetry is centrally planned elements; the four-part garden, the four-part bazaar and caravanserai complex, and the miniature chahar baghs of the inner subsidiary tombs. The mausoleum and the great gate have centralized plans. Each element plays an indispensable part in the whole, if even one of the parts was missing; the balance of the entire composition would be destroyed.

The Principles

PRINCIPLES OF SHAHJAHANI ARCHITECTURE AND AS THEY ARE EXPRESSED IN THE TAJ MAHAL:

The complex of the Taj Mahal explores the potential of the riverfront garden as both an ideal funerary and a utilitarian worldly construct; it also expresses in canonical form the architectural principles of the period.

- Rational and strict geometry.

- Perfect symmetrical planning with an emphasis on bilateral symmetry (qarina) along a central axis of the main features. In a typical Shahjahani qarina scheme two symmetrical features flank a dominant central feature.

- A hierarchical grading of materials, forms and colours.

- Triadic divisions bound together in proportional formulas. These determine the shape of plans, elevations and architectural Ornament.

- Uniformity of shapes, ordered by hierarchical accents.

- Sensuous attention to detail.

- A selective use of naturalism.

- Symbolism.

These principles govern the entire architecture of Shah Jahan. They are expressed most grandly and most consistently in the Taj Mahal.

The Symmetry

The architecture was to express this concept through perfect symmetry, harmonious proportional relationships, and the translucent white marble facing which gives the purity of the geometrical and rational planning the desired unworldly appearance. The mausoleum is raised over an enriched version of the nine-fold plan favoured by the Mughals for tombs and garden pavilions.

A variant is used in the great gate. In the mausoleum the plan is expressed in perfect cross-axial symmetry, so that the building is focused on the central tomb chamber. And the inner organization is reflected on the facades, which present a perfectly balanced composition when seen from the extensions of the axes which generate the plan.

Bilateral symmetry dominated by a central accent has generally been recognized as an ordering principle of the architecture of rulers aiming at absolute power, as an expression of the ruling force which brings about balance and harmony, 'a striking symbol of the stratification of aristocratic society under centralized authority'. A symmetric grading down to the minutest ornamental detail, particularly striking is die-hierarchical use of colour. The only building in the whole complex entirely raced with white marble is the mausoleum. This hierarchic use of white marble and red sandstone is typical of imperial Mughal architecture

The Composition

Thus the entire Taj complex consisted of two components, each following the riverfront garden design; the chahar bagh and terrace; a true riverfront garden and a landlocked variant in the configuration of the two subsidiary units, where the rectangle Jilaukhana corresponded to the riverfront terrace, and the cross-axial bazaar and caravanserai element to the chahar bagh. That lost complex was an integral part of the Taj Mahal, forming its counter-image, according to the basic Shahjahani architectural principle of symmetrical correspondence.

The Design

The historians and poets of Shah Jahan state that the Taj Mahal was to represent an earthly replica of the house of Mumtaz Mahal in the gardens of Paradise. This must not be dismissed as Shahjahani court rhetoric: it truly expresses the programme of the mausoleum. In order to realize the idea of the hatological garden house as closely as possible, the canonical out of previous imperial mausoleums, where the building stood at the centre of a cross-axially planned garden or chahar bagh, is abandoned, and the riverfront design that had become the prevailing residential garden type of Agra was chosen instead, and raised to a monumental scale.

The interaction between residential and funerary genres had characterized Mughal architecture from the beginning. In the Taj Mahal the aim was to perfect the riverfront garden and enlarge it to a scale beyond the reach of ordinary mortals, to create here on earth and in the Mughal city paradisiacal garden palace for the deceased.

Ground Layout of The Taj Mahal Complex

The main north-south axis runs through the garden canal and the bazaar street. On it are set the dominant features: the mausoleum, the pool, the great gate, the Jilaukhana, the southern gate of the Jilaukhana, and the chauk (square) of the bazaar and caravanserai complex.